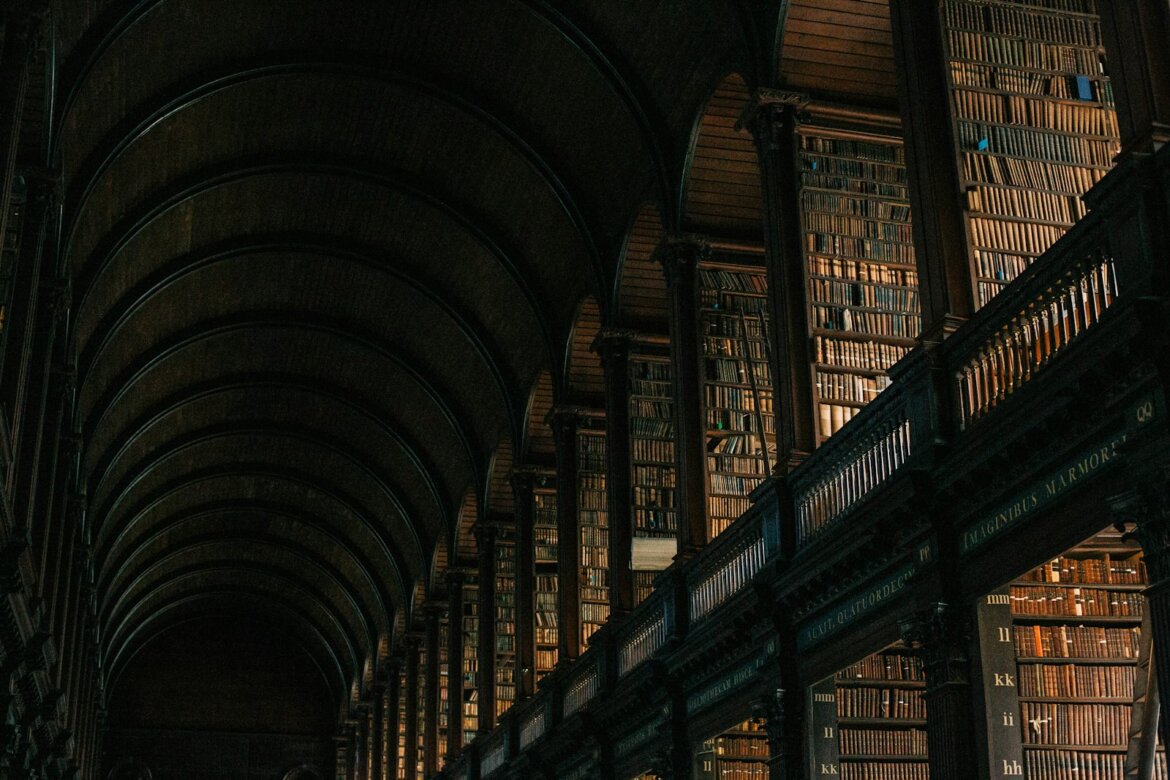

Photo by Bree Anne on Unsplash

Ireland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries experienced an extraordinary flourishing of literary creativity that transformed the island from a cultural backwater into one of Europe’s preeminent centers of artistic achievement. This period, known as the Irish Literary Renaissance or the Celtic Revival, produced some of the greatest literature in the English language and established Ireland as a major force in world literature. Writers of genius emerged in rapid succession: William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, George Bernard Shaw, John Millington Synge, and Lady Gregory created works that revolutionized drama, poetry, and prose. Their achievements remain unsurpassed and continue to influence writers across the world.

The Irish Literary Renaissance coincided with Irish nationalist movements and the struggle for Irish independence. Literature became a vehicle for exploring Irish identity, recovering Irish history and mythology, and imagining an Irish nation free from British rule. Yet the greatest works of this period transcended nationalist concerns to address universal human themes with extraordinary artistry. The result was a body of work that is simultaneously deeply rooted in Irish experience and universally significant.

The Conditions for Renaissance: Nationalism and Cultural Revival

The Irish Literary Renaissance didn’t emerge from nowhere. It was preceded and enabled by the Irish nationalist movement and by growing interest in Irish history, language, and culture. As Irish nationalism intensified in the late 19th century, there was a corresponding impulse to recover and celebrate Irish cultural traditions as a means of asserting Irish identity distinct from English culture.

The founding of the Gaelic League in 1893 was particularly important. This organization worked to revive the Irish language and promote Irish culture as central to Irish identity. Though the Literary Renaissance involved writing in English rather than Irish, the cultural ferment created by the Gaelic League’s work created an environment where Irish writers were encouraged to draw on Irish mythology, language, and cultural traditions.

The Easter Rising of 1916, though a military and political event, profoundly influenced Irish literary culture. The Rising demonstrated the passion and sacrifice of Irish nationalists and inspired writers to create works exploring Irish history, nationalism, and identity. Several important poets, including Patrick Pearse and Thomas MacDonagh, were rebels executed following the Rising, adding to the tragic heroism associated with Irish independence struggle.

Irish independence in 1922 created a new Irish nation and an environment where Irish cultural identity could be fully expressed without the constraints of British rule. Yet paradoxically, the Literary Renaissance had already reached its peak before independence. The greatest works of Yeats and Joyce were completed before or shortly after independence, and the restrictions imposed by the new Irish government on artistic expression meant that the period of greatest literary freedom in Irish history occurred during the struggle for independence rather than after achieving it.

William Butler Yeats: The Towering Giant

No figure looms larger over the Irish Literary Renaissance than William Butler Yeats. Yeats was born in Dublin in 1865 and lived during the entire period of Irish nationalism and independence struggle. His literary career spanned from the 1880s to his death in 1939, encompassing the entire history of the Literary Renaissance and extending beyond it.

Yeats’s early work was influenced by romantic idealism and Irish mythology. He drew heavily on Irish legend and folklore, creating poetry that merged Irish cultural traditions with the formal sophistication of English literary tradition. Works like “The Wanderings of Oisín” demonstrated his ability to transform Irish mythological material into powerful poetry. His play “Cathleen Ní Houlihan” became an iconic nationalist work, with the mysterious woman representing Ireland herself.

Yet Yeats’s greatest work came in his middle and late periods. His collection “The Tower” (1928) and “The Winding Stair” (1933) contain some of the greatest English-language poetry ever written. Poems like “The Second Coming,” “Among School Children,” “Sailing to Byzantium,” and “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop” demonstrate extraordinary technical mastery and profound human insight. These poems, while rooted in Yeats’s experiences and Irish contexts, address universal themes of aging, mortality, desire, and meaning.

Yeats’s influence on English-language literature cannot be overstated. He demonstrated that provincial literature written outside England could achieve the highest levels of artistic achievement. His work inspired generations of poets and influenced the development of modernist literature. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1923, the first Irish person to receive this honor.

Yet Yeats’s relationship to Irish politics and nationalism was complex and sometimes contradictory. While his early work explicitly served nationalist purposes, his later work transcended political concerns. This evolution reflected Yeats’s growing conviction that art was more important than politics and that the artist’s primary duty was to artistic truth rather than political service. This tension between art and politics runs through much Irish literary history.

James Joyce and the Modernist Revolution

If Yeats dominated Irish poetry, James Joyce revolutionized the novel and prose fiction. Joyce was born in Dublin in 1882 and lived during the Literary Renaissance, though his work extended well beyond it and his influence continued to grow long after his death in 1941.

Joyce’s early work, the short story collection “Dubliners,” depicted the lives of ordinary Dublin people with unprecedented realism and psychological insight. Stories like “The Dead,” widely considered one of the greatest short stories in English, captured the complexity of human relationships and the weight of memory and mortality. The collection was important in establishing realistic portrayal of Irish urban life.

Yet Joyce’s true revolutionary achievement came with his novels “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” and especially “Ulysses.” “A Portrait” pioneered techniques of interior monologue and stream of consciousness that would become central to modernist fiction. The novel depicted the spiritual and intellectual development of Stephen Dedalus, and through him, Joyce’s own journey toward artistic independence.

“Ulysses,” published in 1922, is among the most influential and challenging novels ever written. Set in Dublin on June 16, 1904, the novel follows Leopold Bloom, an ordinary Jewish Dubliner, and Stephen Dedalus through a day in the city. On one level, it’s a realistic depiction of Dublin life. On another level, it’s a modernist masterpiece employing multiple literary techniques and styles. The novel’s exploration of consciousness, its stylistic innovations, its frank discussion of sexuality, and its profound human insight made it revolutionary.

The publication of “Ulysses” was controversial. Its frank discussion of bodily functions and sexual desire scandalized many readers. It was banned in several countries, including Ireland and the United States, for its obscenity. The legal battles over the novel’s publication became famous, with American judge John Woolsey’s 1933 decision upholding the novel’s literary merit and allowing its American publication being celebrated as a victory for artistic freedom.

Joyce’s final work, “Finnegans Wake,” published in 1939, was even more experimental. Written in a language that Joyce himself invented, blending English with elements of dozens of other languages, the work is notoriously difficult and remains largely inaccessible to most readers. Yet its ambition and innovation are remarkable, and scholars continue to explore its meanings.

Joyce is often not considered an “Irish” writer in nationalist terms. He lived much of his life outside Ireland, expressed skepticism about Irish nationalism, and created works that transcended Irish parochialism to address universal human concerns. Yet Joyce’s work is thoroughly rooted in Dublin, Irish experience, and Irish culture. His achievement demonstrated that Irish writers could operate at the highest levels of international modernism while remaining deeply connected to their Irish origins.

George Bernard Shaw: The Drama of Ideas

While Yeats and Joyce represented Irish literary achievement in poetry and fiction, George Bernard Shaw demonstrated Irish excellence in drama. Shaw, born in Dublin in 1856, became one of the great dramatists of the English-speaking world. Though he spent most of his life in England, he remained identified with Ireland and Irish culture throughout his career.

Shaw’s plays were revolutionary in their commitment to using drama as a vehicle for exploring ideas and social issues. Earlier dramas had emphasized plot and emotion, but Shaw created plays where intellectual debate and social commentary were central. Works like “Arms and the Man,” “Pygmalion,” and “Saint Joan” combined dramatic structure with serious exploration of important themes.

Shaw’s wit and verbal facility made his plays entertaining even as they addressed serious issues. Audiences could enjoy the comedy and the clever dialogue while also engaging with the serious ideas beneath. This combination of entertainment and intellectual substance gave Shaw’s work broad appeal and lasting influence.

“Pygmalion,” Shaw’s most famous play, tells the story of a linguist who bets that he can transform a poor flower girl into a duchess by teaching her to speak properly. On the surface, it’s a charming love story. But it’s also a sophisticated exploration of class, gender, language, and power. The play’s final scene, deliberately ambiguous about whether the main characters will actually marry, raises unsettling questions about love, marriage, and the female protagonist’s agency.

Shaw’s work was often controversial, particularly in Ireland, where his skepticism about religion and his sexual libertarianism offended conservative Catholic sensibilities. Yet his dramatic achievement was undeniable, and he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1925, only two years after Yeats’s achievement of the same honor.

The Abbey Theatre and Synge’s Rebellion

The Abbey Theatre, founded in 1899 by Lady Gregory and others, became the institutional center of Irish drama. The theatre was dedicated to presenting Irish plays by Irish playwrights and quickly became associated with the Literary Renaissance. Many of the greatest Irish plays were first performed at the Abbey Theatre.

The theatre’s commitment to Irish drama was complicated by questions about what constituted appropriately “Irish” plays. This question came to a head with John Millington Synge’s plays, particularly “The Playboy of the Western World.” Synge’s work, which used dialect speech and depicted Irish rural life with linguistic authenticity, shocked audiences who felt that his portrayal was demeaning to Irish people and culture.

Synge had spent years in the Irish-speaking Aran Islands, learning Irish and studying Irish life. He incorporated this authentic knowledge of Irish speech patterns and rural culture into his plays. Yet Irish audiences found his portrayal of Irish people—rough, crude, passionate, sometimes violent—offensive and un-Irish.

“The Playboy of the Western World” sparked riots at the Abbey Theatre when it premiered in 1907. Audiences felt the play demeaned Irish dignity and femininity. Critics argued that it reinforced English stereotypes about wild, uncivilized Irish people. Yet Synge’s dramatic artistry and his authentic depiction of Irish speech and culture made the play a masterpiece despite—or perhaps because of—its controversial portrayal of Irish life.

The controversy over “The Playboy” reveals tensions within the Literary Renaissance between nationalist desire to celebrate Irish culture and modernist commitment to artistic truth and authenticity. Synge believed the artist should depict life truthfully rather than as nationalists wished it to be. This conflict between artistic integrity and political/national identity remained unresolved.

Lady Gregory and the Recovery of Irish Culture

Lady Augusta Gregory was a crucial figure in the Literary Renaissance, though her role was sometimes overshadowed by male writers. Gregory was an Anglo-Irish woman of the landlord class who dedicated her life to preserving and celebrating Irish culture. She founded the Abbey Theatre with Yeats and others, and her work as a dramatist, folklorist, and cultural activist made her central to the Literary Renaissance.

Gregory’s plays, often written for the Abbey Theatre, drew on Irish folklore and rural culture. Her work “The Workhouse Ward” and others demonstrated her ability to capture Irish rural speech and experience. She was also important as a patron and supporter of other writers, promoting their work and helping to establish them.

Gregory’s work as a folklorist, collecting and publishing Irish folklore and stories, contributed significantly to the recovery of Irish cultural traditions. Her collections of folklore preserved stories, songs, and cultural knowledge that might otherwise have been lost. This recovery work was important to the broader nationalist and cultural revival project.

The Broader Renaissance: Poetry and Other Voices

Beyond Yeats, Joyce, Shaw, and Synge, the Irish Literary Renaissance produced numerous other significant writers. In poetry, figures like Thomas Yeats (William Butler Yeats’s brother), AE (George Russell), and later poets continuing the tradition created important work exploring Irish themes and employing sophisticated poetic techniques.

In prose, besides Joyce, writers like Liam O’Flaherty, Sean O’Casey, and others created important works exploring Irish experience. O’Casey’s plays dealing with Irish nationalism and Dublin working-class life brought those experiences to the dramatic stage. These writers, while perhaps not achieving the towering achievement of Yeats or Joyce, contributed significantly to the Literary Renaissance.

The women writers of the period deserve particular mention. While male writers have often been more celebrated, women writers like Lady Gregory, Sarah Allgood, and others contributed significantly to Irish literary achievement. Later periods would produce more prominent female Irish writers, but during the Renaissance period, women’s contributions were important even if sometimes overshadowed.

The Influence and Legacy

The Irish Literary Renaissance transformed world literature. The techniques developed by Joyce and other modernist writers influenced the development of the novel throughout the 20th century. Yeats’s poetry demonstrated that modernist poetry could achieve both intellectual sophistication and emotional power. Shaw’s drama showed that plays could be vehicles for serious intellectual debate.

Irish writers proved that a provincial literature, rooted in a specific place and culture, could achieve universal significance and international influence. Irish writers demonstrated that writing in English from Ireland didn’t mean imitating English models but could involve creating genuinely original and revolutionary work.

The Renaissance also demonstrated the interconnection between literature and nationalism. While the greatest work transcended explicit nationalist purposes, the nationalist ferment and the project of recovering Irish culture created the environment in which the Renaissance flourished. Literature became a vehicle for asserting Irish identity and imagining Irish independence in ways that complemented the political struggle.

The Darker Side: Censorship and Restriction

Yet it’s important to note that the Irish Literary Renaissance occurred in tension with censorship and restriction. Many important Irish literary works were banned by Irish authorities for obscenity or perceived immorality. The Irish Free State, established in 1922, soon imposed significant censorship restrictions on literary works.

Joyce’s “Ulysses” was banned in Ireland. Samuel Beckett’s works, while not banned, were controversial. Works dealing frankly with sexuality, doubt, or irreverence to religion faced censorship or boycotts. This irony—that a nation struggling for independence to assert its own values would then restrict artistic expression—troubled many Irish writers and intellectuals.

The censorship of Irish literature by Irish authorities revealed conflicts between conservative Catholic values and modernist artistic values. It also suggested that literary freedom, even after achieving political independence, could be restricted by authorities claiming to represent national values. This tension between artistic freedom and conservative cultural values would persist in Irish literature and society.

Conclusion: The Extraordinary Achievement

The Irish Literary Renaissance represents one of the great achievements in world literature. In a remarkably concentrated period of time, Ireland produced literary works of genius that transformed English-language literature and influenced world culture. Writers like Yeats, Joyce, Shaw, and Synge created works that remain essential to understanding modernism, that continue to influence writers, and that command the attention and respect of readers across generations and cultures.

This achievement is remarkable given Ireland’s position as a relatively small, colonized nation struggling for independence. Yet the combination of cultural nationalism, the recovery of Irish traditions, the wealth of Irish literary and cultural resources, and the presence of writers of genuine genius created conditions for the extraordinary flourishing of Irish letters.

For Americans interested in Irish culture and heritage, the Literary Renaissance is essential. It demonstrates the depth of Irish cultural achievement and the profound contributions of Irish writers to world literature. It shows that Irish culture produced works of universal significance and that Irish identity, far from being provincial or limited, was capable of engaging with the most sophisticated artistic and intellectual traditions of the age.