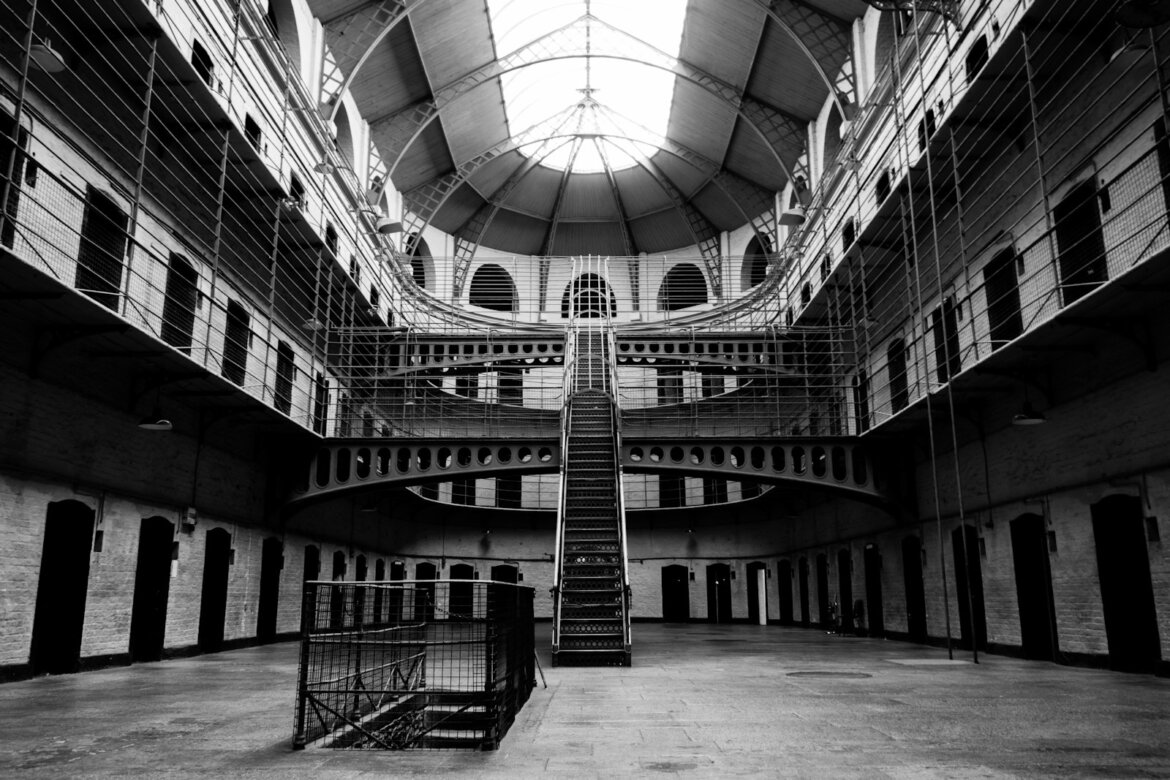

Photo by Yoav Aziz on Unsplash

In the centuries following the English conquest of Ireland and the Protestant Reformation, a systematic legal framework was created to restrict and oppress the Catholic Irish population. These laws, collectively known as the Penal Laws or Popery Laws, created a comprehensive system of discrimination against Catholics, restricting their rights to own land, practice their religion, receive education, hold office, and participate in numerous other aspects of civic and economic life. Operating over nearly two centuries, from roughly the 1650s through the 1770s, the Penal Laws represented one of history’s most comprehensive attempts to use law to subjugate and marginalize an entire population based on religious belief. Understanding the Penal Laws is essential to understanding the conditions that shaped Irish society and culture in this critical period.

Origins and Motivations

The Penal Laws did not appear suddenly but developed gradually in response to specific historical circumstances. Following the Irish Rebellion of 1641, in which Irish Catholics rebelled against English rule and Protestant settlement, the English authorities moved to consolidate their control over Ireland and prevent future rebellions. The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649-1653) brought brutal subjugation, with significant numbers of Irish people killed and entire classes of Irish society displaced from their lands.

The Restoration of Charles II (1660) brought a period of relative religious tolerance, but the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89 changed the political situation fundamentally. The deposition of James II, a Catholic monarch, in favor of the Protestant William III, created a crisis of succession and loyalty. Because James II’s son was Catholic, Protestant powers feared that unless action was taken, a Catholic monarch might return to power. The result was the reinforcement and elaboration of legal restrictions on Catholics throughout the English Empire.

In Ireland specifically, the Williamite Wars (1688-1691), fought between armies loyal to the deposed James II and forces supporting William III, ended with the victory of William’s forces. The Treaty of Limerick (1691) supposedly granted some protections to Catholics, but these were largely ignored. In the years following the Williamite Wars, Irish Protestant authorities moved systematically to enact a comprehensive legal code restricting Catholic rights and power.

The motivations behind the Penal Laws were mixed. Partly they reflected Protestant anxiety about Catholic power and a genuine fear of Catholic rebellion and restoration of a Catholic monarchy. Partly they reflected the economic interests of the Protestant elite, who wished to consolidate their control of land, property, and political office. Partly they reflected religious conviction—the belief that Protestantism was religiously superior and should be promoted and protected. The result was a legal system that served multiple purposes: political control, economic exploitation, and religious domination.

Restrictions on Land Ownership

Among the most economically consequential of the Penal Laws were the restrictions on Catholic land ownership and inheritance. Under these laws, Catholics were severely restricted in their ability to purchase land or to lease land on favorable terms. More importantly, Catholic landholdings were subject to particular inheritance rules designed to fragment Catholic-owned estates.

The laws provided that when a Catholic landowner died, his lands were to be divided equally among all his sons, rather than following the English custom of primogeniture (inheritance by the eldest son). This practice of subdivision upon each generation meant that Catholic estates, unlike Protestant estates that remained intact through inheritance by the eldest son, became progressively fragmented into smaller and smaller parcels. Over generations, this fragmentation reduced the economic power and influence of the Catholic landed classes.

Additionally, Catholics were subject to restrictions on leasing land. A Catholic could not lease land for a period longer than thirty-one years, which meant that even if a Catholic gained the use of land, he could not develop long-term plans for improving it. These lease restrictions made it difficult for Catholics to engage in long-term agricultural improvement or to invest substantially in the land they worked.

The consequence of these land restrictions was a dramatic shift in land ownership in Ireland. At the beginning of the Penal Law period (roughly 1690), Catholics owned approximately sixty percent of Irish land. By the end of the Penal Law period (1778), this had been reduced to approximately five percent. This enormous transfer of property from Catholic to Protestant hands was one of the most dramatic economic transformations in Irish history.

Religious Restrictions

The Penal Laws also included comprehensive restrictions on Catholic religious practice. Catholic churches were forbidden or restricted, and Catholics were prohibited from celebrating Mass publicly. Priests were forbidden from exercising their functions, and Catholic bishops were expelled from Ireland. The hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Ireland was effectively displaced, and the functioning of Catholic religious institutions was driven underground.

However, the laws could not be completely enforced. Catholic communities maintained secret priests who celebrated Mass in private homes or outdoors at remote locations. Catholic bishops remained in Ireland despite the prohibition, hiding from authorities and maintaining church organization. Catholics developed a tradition of holding Mass in remote locations, sometimes at standing stones or other ancient sites that had acquired religious significance, to avoid detection.

The restriction on public worship meant that Catholics could not openly exercise their religious practices and were forced to hide or minimize religious expression. This created a situation where Catholic religion went underground, where it was associated with resistance to English rule, and where adherence to Catholicism became a matter of identity and defiance rather than merely a religious preference.

Educational Restrictions

The Penal Laws also restricted Catholic access to education. Catholics were forbidden from attending educational institutions within Ireland that taught religious subjects, and they were prohibited from becoming teachers. The intention was to prevent Catholic children from receiving education that would transmit Catholic beliefs and to cut off the transmission of Catholicism through education.

These restrictions had profound consequences. The Catholic Irish elite, for centuries educated in Irish schools and monasteries, now had to send their sons abroad to continental Europe to receive an education. This created a class of exiled Irish—young men educated in Spain, France, and other continental Catholic countries, who often did not return to Ireland. This brain drain of educated Irish represented a significant loss of intellectual capital to Ireland.

The educational restrictions also meant that literacy, particularly in English, became less common among the Catholic Irish population. This created a growing gap between the English-speaking, educated, largely Protestant elite and the Irish-speaking, increasingly illiterate Catholic masses. The consequence was a growing cultural divide in Ireland, with English culture and language dominating among the powerful, while Irish language and culture persisted among the powerless.

Professional and Political Restrictions

The Penal Laws also excluded Catholics from most professions and from political participation. Catholics were forbidden from becoming lawyers, judges, or senior government officials. They could not serve as officers in the military. They could not hold most corporate positions. These restrictions meant that entire professions and sources of advancement were closed to Catholics.

Additionally, Catholics were excluded from participation in Parliament and could not vote in elections. This disenfranchisement meant that Catholics had no voice in the political processes that governed their own country. Laws affecting them were made by exclusively Protestant representatives, with no Catholic input. This created a system where one religious group held complete political power while the other was entirely excluded.

Social and Legal Discrimination

Beyond the major categories of restriction, the Penal Laws included numerous smaller restrictions and discriminatory provisions. Catholics had to pay additional taxes and tithes to support the established Protestant Church of Ireland, even though they did not attend or benefit from that church. Catholics were forbidden from carrying weapons or holding hunting rights. Catholics could not breed horses valued above a certain amount.

These smaller restrictions were partly practical measures to limit Catholic military potential and economic resources, but they also served a broader function of humiliation and marginalization. They communicated to Catholics that they were subject peoples, living in their own country under restrictions that free people did not face.

The Penal Laws also created perverse incentives that operated throughout Irish society. A Catholic who conformed to Protestantism—who publicly converted and attended the established Church of Ireland—could escape the restrictions. This created a situation where some Catholics formally converted to escape the legal disabilities, though many maintained Catholic belief privately. It also created a system where informants and informing were incentivized, as people could gain rewards by reporting violations of the Penal Laws.

Social Effects and Economic Consequences

The cumulative effect of the Penal Laws was to reduce the Catholic Irish population to a state of legal and economic subjugation. Catholics were excluded from political power, restricted in economic opportunities, and subject to systematic legal discrimination. The wealth and land that had once been distributed among Catholics was transferred to Protestants.

Additionally, the Penal Laws contributed to economic stagnation and poverty in Ireland. By preventing Catholics from owning land, improving property, or engaging in lucrative professions, the laws restricted economic development in much of Ireland. The result was a society increasingly characterized by poverty, landlessness, and dependence on Protestant landlords. This economic gap between Catholic peasants and Protestant gentry became a defining feature of Irish society.

The laws also created resentment and alienation. Catholics were clearly and explicitly defined as unequal, as incapable of self-governance, as threats to the established order. This stigmatization and marginalization contributed to the development of a strong Irish Catholic identity, defined partly in opposition to Protestantism and English rule.

Gradual Relaxation

The Penal Laws were gradually relaxed beginning in the 1770s. Various reasons contributed to this relaxation: the American Revolution, which demonstrated the dangers of maintaining an alienated population without rights; the rise of enlightened thought that questioned the legitimacy of religious discrimination; the recognition that enforcing the Penal Laws required more effort than many authorities wished to invest; and the development of a more economically progressive class of Irish Protestant gentry who saw that Catholic economic participation might be beneficial to Irish development.

The Catholic Relief Acts of the 1770s, 1780s, and 1790s gradually expanded Catholic rights. Restrictions on land ownership were removed. Restrictions on religious practice were relaxed. Catholic participation in some professions was permitted. Finally, with Catholic Emancipation in 1829, most legal restrictions on Catholics were formally removed, though some discrimination persisted informally.

Legacy and Meaning

The Penal Laws left a profound mark on Irish society and culture. They created a class structure that persisted long after the laws themselves were repealed, with Catholics concentrated in landless, impoverished classes and Protestants concentrated in the land-owning, more prosperous classes. They contributed to the development of Irish nationalism, as Catholics came to see themselves as an oppressed nation under English rule.

The Penal Laws also shaped Irish American identity. Many Irish immigrants to America fled the poverty and oppression that the Penal Laws had created. The memory of the Penal Laws and the oppression they represented became part of Irish American consciousness, contributing to the political radicalism and anti-English sentiment that characterized much of Irish American history.

The experience of the Penal Laws also demonstrated the power of law as an instrument of oppression. The systematic use of law to restrict rights, to transfer property, and to marginalize a population showed how legal systems could be weaponized to serve oppressive purposes. This history has resonated in broader discussions of civil rights, discrimination, and the power of law.

Understanding the Penal Laws is essential to understanding Irish history, the roots of Irish-English conflict, the development of Irish nationalism, and the conditions that drove Irish emigration to America. The laws represented a comprehensive attempt to use law to subjugate an entire population based on religion, and their effects—both in the immediate period and in the long-term consequences—shaped the trajectory of Irish history for centuries.