Every March 17th, a sea of green sweeps across Ireland and much of the world. Streets fill with parades, pubs overflow with revelers, and landmarks from the Sydney Opera House to the Empire State Building glow emerald in the night. In Chicago, they even dye the river green! St. Patrick’s Day has transcended its origins as a religious feast day to become a worldwide celebration of Irish culture and heritage. But beneath the green beer and shamrock face paint lies a rich history and cultural significance that speaks to the resilience of Irish identity both at home and abroad.

The Man Behind the Myth

To understand St. Patrick’s Day, we must first understand the man himself—separating fact from the many legends that have grown around his name over the centuries.

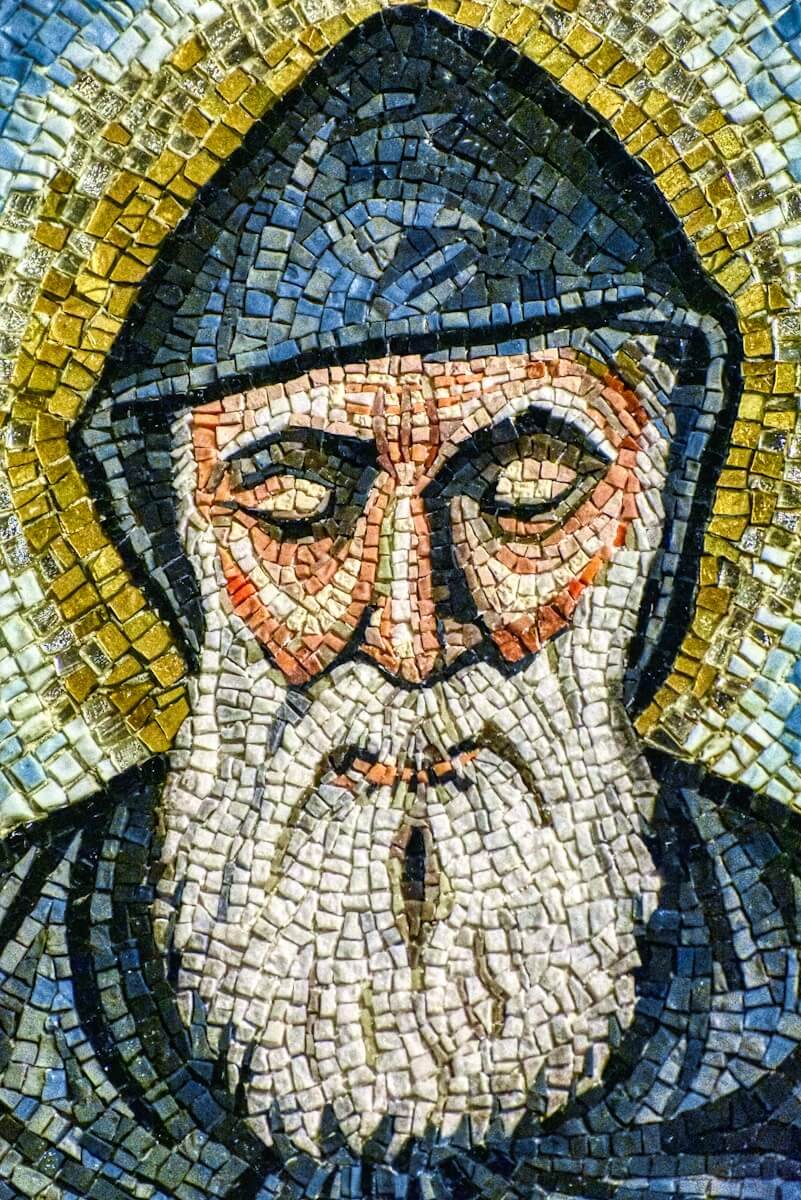

Contrary to popular belief, Patrick was not Irish by birth. Born in Roman Britain around 385 CE, he was kidnapped at age 16 by Irish raiders and forced into slavery in Ireland. After six years as a shepherd, he escaped and returned to Britain, where he later joined the church. According to his autobiographical “Confession,” Patrick experienced a vision calling him to return to Ireland as a missionary.

Around 432 CE, he did just that, spending the remainder of his life converting the pagan Irish to Christianity. While legends credit him with driving snakes from Ireland (a country that never had snakes) and using the three-leaved shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity, historians view these as allegorical tales that developed long after his death, believed to have occurred on March 17, 461 CE.

Patrick never officially received canonization through the modern process, but was declared a saint by popular acclaim. His feast day became a fixture in the early Irish church calendar, marking the anniversary of his death.

From Religious Observance to National Holiday

For centuries, St. Patrick’s Day was primarily a religious occasion in Ireland—a holy day of obligation for Catholics, who attended Mass to honor their patron saint. The day fell during Lent, when Catholics abstained from meat and often alcohol, but these restrictions were lifted for the feast day, perhaps contributing to its later association with revelry.

The transformation of St. Patrick’s Day into a public celebration began not in Ireland but among the Irish diaspora, particularly in America. The first recorded St. Patrick’s Day parade took place in Boston in 1737, organized by the Charitable Irish Society. New York City’s parade, now the world’s largest, began in 1762 when Irish soldiers serving in the British Army marched through the city.

In Ireland itself, St. Patrick’s Day remained a relatively modest religious holiday until the mid-20th century. The day was declared a national holiday in 1903, but pubs were mandated by law to close on March 17th until 1970—a stark contrast to the alcohol-centric celebrations seen today.

The modern Irish celebration began to take shape in 1996 with the first official St. Patrick’s Festival in Dublin, a government initiative to showcase Ireland to the world and drive tourism. What began as a one-day celebration has expanded to a five-day festival drawing over a million visitors.

Cultural Significance in Ireland

Despite its evolution and commercialization, St. Patrick’s Day retains deep cultural significance for the Irish people. It represents a moment of national unity and pride—a day when Ireland celebrates not only its patron saint but its unique cultural identity.

The day serves as a powerful reminder of Ireland’s historical journey. The nation’s history is marked by periods of invasion, colonization, famine, emigration, and struggle for independence—experiences that have shaped Irish identity. St. Patrick’s Day offers an opportunity to reflect on this heritage while celebrating Ireland’s contributions to world literature, music, art, and thought.

For many Irish families, the day begins with Mass, followed by attendance at a local parade. Communities across the country, from Dublin to the smallest villages, organize parades featuring marching bands, elaborate floats, street performers, and community groups. Traditional Irish music and dance performances are common features of these celebrations.

The wearing of green, Ireland’s national color, is ubiquitous—from clothing to face paint to the dyeing of rivers and beer. The shamrock remains a central symbol, worn proudly on lapels and hats. Traditional foods like Irish stew, colcannon, and soda bread feature prominently on family tables.

While tourism and commercial interests have undoubtedly shaped the modern celebration, many Irish people view the day as an important connection to their heritage and an opportunity to share that heritage with the world.

St. Patrick’s Day and the Global Irish Diaspora

Perhaps nowhere is St. Patrick’s Day celebrated with more enthusiasm than among the Irish diaspora—the estimated 70 million people worldwide who claim Irish ancestry. This global community, formed through centuries of emigration driven by famine, economic necessity, and political circumstances, has kept Irish culture alive across continents.

For the diaspora, St. Patrick’s Day serves as a powerful connection to an ancestral homeland many have never visited. It offers an opportunity to express cultural pride and maintain ties to Irish heritage through generations of separation.

The United States, home to approximately 32 million people of Irish descent, hosts some of the world’s largest St. Patrick’s Day celebrations. Chicago famously dyes its river green, while New York’s Fifth Avenue parade draws approximately two million spectators. Boston, with its strong Irish-American community, transforms the day into a citywide celebration.

But the Irish diaspora extends far beyond America. In Canada, Montreal has held a parade since 1824. Australia, with its significant Irish population dating back to the colonial period, hosts major celebrations in Sydney and Melbourne. Even in Argentina, home to one of South America’s largest Irish communities, the day is marked with festivals and gatherings.

The global spread of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations reflects the extraordinary reach of Irish emigration and the resilience of Irish cultural identity across time and distance. For many in the diaspora, the day offers a tangible connection to an ancestral homeland and an affirmation of belonging to a global Irish community.

Modern Celebrations: Evolution and Commercialization

Today’s St. Patrick’s Day celebrations represent a complex blend of tradition, innovation, and commercial interests. The holiday has evolved far beyond its religious origins to become one of the world’s most recognized cultural celebrations.

In Dublin, the St. Patrick’s Festival has grown into a multi-day spectacle featuring elaborate parades, light shows, street performances, and music festivals. The event draws visitors from around the world and generates significant tourism revenue—an estimated €73 million in 2019 alone.

The “Global Greening” initiative, launched by Tourism Ireland in 2010, has seen hundreds of iconic landmarks worldwide illuminated in green on March 17th—from the Colosseum in Rome to the Great Wall of China, the Sydney Opera House to the Empire State Building. This visual spectacle has become a powerful marketing tool for Irish tourism.

The commercialization of St. Patrick’s Day has been most pronounced in the United States, where it has evolved into one of the year’s biggest drinking holidays. American beer companies, particularly those with Irish connections like Guinness, have capitalized on and fueled this association. The result is often a version of Irish culture that many in Ireland view as stereotypical or caricatured.

This commercialization has not been without controversy. Many Irish and Irish-Americans have expressed concern about the portrayal of Irish culture as centered on alcohol, the use of stereotypical imagery like leprechauns, and the reduction of a complex cultural heritage to simplistic symbols. Some argue that the authentic meaning of the day has been lost amid green beer and plastic shamrocks.

Yet others suggest that the global popularity of St. Patrick’s Day, however commercialized, has helped preserve Irish cultural awareness and created opportunities to introduce authentic aspects of Irish heritage to wider audiences.

Cultural Diplomacy and Soft Power

Beyond its significance for Irish communities, St. Patrick’s Day has become an extraordinary tool of cultural diplomacy and soft power for Ireland. Few nations of Ireland’s size enjoy an annual day when their culture is celebrated worldwide.

The Irish government has strategically leveraged this global attention. Each year, Irish politicians travel to major international cities for St. Patrick’s Day, gaining access to key political figures and media platforms. The traditional presentation of a bowl of shamrocks to the U.S. President has ensured Ireland regular access to the White House—invaluable for a small nation.

This cultural diplomacy has helped Ireland project influence beyond its size, strengthening its position within the European Union, attracting foreign investment, and promoting tourism. St. Patrick’s Day celebrations have also provided platforms to showcase contemporary Irish culture, challenging outdated stereotypes and highlighting Ireland’s modern creative industries, technological innovation, and progressive social changes.

The day has occasionally served as a vehicle for political messages as well. During the Northern Ireland peace process, St. Patrick’s Day celebrations in the United States created opportunities for dialogue and advocacy. More recently, the day has been used to promote awareness of Irish language revival efforts and environmental initiatives.

Preserving Authenticity in a Global Celebration

As St. Patrick’s Day continues to evolve as a global phenomenon, questions of authenticity and cultural representation remain central. How can a celebration maintain its cultural integrity while embracing its worldwide appeal?

In Ireland, there has been a conscious effort to reclaim the day’s cultural significance beyond stereotypes and commercialization. The St. Patrick’s Festival in Dublin now incorporates substantial arts programming, including literary events, film screenings, and exhibitions of contemporary Irish art. Many communities emphasize family-friendly celebrations that showcase authentic Irish music, dance, language, and crafts.

Within the diaspora, cultural organizations work to balance popular festivities with educational components that deepen understanding of Irish history and heritage. Irish language classes, traditional music workshops, and historical exhibitions increasingly accompany the parades and parties.

Digital platforms have created new opportunities to share authentic Irish culture globally on St. Patrick’s Day. Virtual concerts, online language lessons, and streaming cultural programs allow people worldwide to engage with contemporary Irish culture beyond stereotypes.

This tension between commercialization and authenticity, between global appeal and cultural specificity, is likely to remain a defining feature of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations. Yet this very tension reflects the dynamic nature of cultural heritage in a globalized world—constantly negotiated, reimagined, and renewed through celebration.

A Day of Connection

At its heart, St. Patrick’s Day endures because it fulfills a profound human need for connection—to heritage, to community, to shared history. For the Irish at home, it offers a moment to celebrate national identity after centuries of struggle to preserve it. For the diaspora, it provides a tangible link to ancestral roots across oceans and generations. For those with no Irish connection, it presents an invitation to participate in a celebration that transcends borders.

The evolution of St. Patrick’s Day from religious feast to global phenomenon reflects the extraordinary journey of the Irish people themselves—from a small island nation to a global cultural presence. That a fifth-century missionary’s feast day has become an international celebration of cultural heritage speaks to both the historical reach of Irish emigration and the universal appeal of Irish culture.

As March 17th continues to be marked by parades and parties around the world, it carries with it this complex legacy—of faith and folklore, of hardship and resilience, of cultural preservation against long odds. Behind the revelry lies a story of identity maintained across distance and time, a testament to the enduring power of cultural heritage in our global age.