Ireland’s Great Famine of 1845-1849 has left a searing wound on the country’s history. This national tragedy decimated the Irish population, killing over a million men, women and children, and prompting one million more to emigrate to Britain and the Americas. The apparent inaction and incompetence of the British government in failing to mitigate the crisis fuelled a widespread current of anger and resentment that gave succour to repealers and Irish nationalists and paved the way for the sectarian violence of the early 20th century. The origins, events and implications of the famine remain the source of considerable debate, and the trauma of this terrible event has not yet been expunged from Ireland’s national psyche.

Key Facts

Key Dates

- 1 August 1800 Act of Union between Great Britain and Ireland

- October 1845 First potato crop fails

- 29 July 1849 Young Irelander Rebellion

- 2 – 12 August 1849 Queen Victoria visits Ireland

Key Figures

- Bridget O’Donnell Famine victim featured in the London Illustrated News

- Sir Robert Peel British Prime Minister 1841-1846

- John Russell British Prime Minister 1846-1852

- Charles Edward Trevelyan Secretary to the Treasury/Administrator during the Famine

- Queen Victoria British Monarch 1837-1901

Incompetent Landlords and Feckless Tenants: Ireland’s Land Crisis

The Irish potato famine was caused, ostensibly, by a devastating potato blight that swept through the Americas and Europe in the 1840s. This caused the potato crop to fail in successive years, but why did this lead to such a crippling famine in Ireland, and not elsewhere? Other countries on the continent suffered extensive loss of potato crops but did not experience a fraction of the devastation wreaked upon Ireland’s poor. This is the central question that has animated the study of the famine over the course of the past 160 years: why did the failure of this single crop lead to such a catastrophic human disaster?

The long-term origins and causes of the Great Irish Famine lay in the system of landholding that had developed in Ireland over the course of the 18th century, and the historic marginalisation of the Catholic population. During the 17th century, Irish Catholics had been prohibited from landholding, excluded from law and governance, had limited access to education, and were unable to practice their religion freely. Although these discriminatory laws were abolished as part of Catholic Emancipation in 1829, permanent damage had been inflicted on Irish society, creating a large, impoverished peasant class that was primarily composed of indigenous Catholics who worked as tenant farmers. The landed gentry, on the other hand, comprised English and Anglo-Irish Protestant elites who held vast estates across the country.

This two-tier structure in Irish society caused significant social tensions. In the early 1840s, Daniel O’Connell, a charismatic and articulate lawyer from County Kerry, led the increasingly loud calls for repeal of the 1800 Act of Union, calling for an independent Irish government and fair representation of Irish Catholics. It was estimated that in this period, approximately 2.4 million people across the country lived in poverty, many of them driven into destitution by unfair treatment meted out by landlords and their ‘middlemen’, employees who managed their estates. Two-thirds of the Irish population were completely dependent on agriculture, but they were rarely able to sustain themselves and their families. The middlemen were given unlimited powers to raise rents, evict tenants, and reclaim land. This lack of security of tenure meant that tenant farmers were often left with very small patches of land that were insufficient to support them and their families.

The landholding system of tenure in Ireland different substantially to that of England. This was not a paternalistic system in which tenant farmers were protected by landholders and felt a sense of obligation and loyalty. Rather, the Irish Catholic population saw themselves as an occupied nation, exploited and abused by an Anglo-Protestant elite. This led to a volatile situation, which was recognised by the British in an inquiry of 1843. In Westminster, the prevailing view was that Ireland needed significant land reform and modernisation, despite opposition from recalcitrant landlords and (in their view) lazy tenants.

Why the Potato? Monoculture and the Effects of the Blight

Potatoes had been introduced to Ireland in the 17th century, but in the early 18th century they began to dominate in poorer communities. The potato offered a number of advantages for impoverished farmers: it could feed families through the winter, was easy to grow, and could be cultivated in small plots of land. As Irish farmers faced increasing hardship, they became increasingly dependent on potatoes as their main food staple. In part, this was due to the fact that much of the good arable land in the Irish countryside was devoted to raising cattle, leaving tenant farmers with only poorer, marginal land that could not sustain a variety of crops. These factors led to a situation of monoculture: varieties of potato in Ireland were limited to one or two genetic variations, and there was an overreliance on the potato crop among approximately two-thirds of the Irish population.

The potato was not always, however, a reliable source of food. Throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the potato crop in Ireland had frequently failed due to disease and poor weather, forcing the government to take action in order to redistribute food and prevent unrest. As the population became more and more reliant on this crop, the threat of famine loomed.

In 1843 and 1844, a viral pathogen originating in Mexico decimated potato crops in North America. By 1845 it had spread rapidly around Europe, causing the harvest to fail in Belgium, Holland and France. When it came to the harvest in Ireland in October of 1845, it became clear that between 35 and 50% of the crop had been lost. Despite hopes that the situation would be alleviated by the next harvest, in the following year, 75% of the crop was affected, leaving so few seed potatoes that it became clear that there would be no harvest in 1847. The years of hunger had begun.

Response

The governmental response to the Irish famine was conditioned by a number of prevailing assumptions in Westminster about the problems afflicting Ireland’s system of landholding. The British believed that the Irish peasantry was lazy, indolent and prone to violence, and their reliance on the potato was a reflection of their poor work ethic. They also wished to overhaul the out-dated system of landholding and tenancy and to force a crisis that would pave the way for reform. From this perspective, supplying aid to the Irish peasant population would simply perpetuate the problem and increase reliance. In some circles, concern was expressed that the Irish would simply take advantage of British prosperity and wealth. From the outset, therefore, British assumptions about the causes and nature of the crisis had a significant effect on the way in which it was handled, and the extent of aid that would be offered.

Nevertheless, it should not be suggested, as some nationalist narratives contest, that the British withheld food aid in order to purposefully decimate the Irish population and inflict genocide. In the first year of the crisis, the British Prime Minister Robert Peel did arrange for large shipments of cornmeal from the Americas, but this was poorly distributed, difficult to mill and digest, and soon ran out. Peel also attempted to repeal the Corn Laws, tariffs on grain imports that were intended to keep domestic grain prices (and therefore bread) artificially high. This issue caused a schism in the Tory Party, and Peel was forced to resign. Although grain imports increased and prices fell, this measure was not enough to ameliorate the situation for Ireland’s poorest.

Peel’s successor, John Russell, was committed to the economic principle of laissez-faire, meaning that he and his government favoured limited intervention in economic matters. Russell believed that mass imports of food aid would cause imbalances in the Irish economy and that limits on exports would cause an undesirable fall in prices. The English administrator, Charles Edward Trevelyan, who oversaw the situation in Ireland, explicitly halted Peel’s imports of corn from America in order to prevent the Irish from becoming “habitually dependent” on the English. Free market principles, it was thought, would kick in and stabilise the situation.

As a result, in an ironic twist, Ireland continued to produce large quantities of grain and other foodstuffs throughout the famine, which were exported from ports where the local population lay starving. In essence, Ireland’s Great Famine was not caused by lack of food throughout the country, but rather by high costs and abject poverty, which prevented the poor majority from feeding themselves and their families.

At the crisis worsened in 1847, increasing numbers of starving Irish peasants were evicted from their homes, leaving them with little choice but to leave the country. In such circumstances, many Irish landlords actually paid for their tenants to leave the country on so-called ‘coffin ships’ headed for North America. Tenants were thrown off their land, promised money and food, and then packed into overcrowded ships leaving the west coast. On their arrival in Canada or the United States, if they survived the perilous journey, the promised food and shelter didn’t materialise, and they were left to eke out a living in whatever way they could in their new home. Approximately 1 in 5 passengers did not survive this journey. Other refugees ended up in Britain, or worse, were deported back to Ireland, where they faced utter destitution, disease, and aching hunger.

The Human Face: The Tale of Bridget O’Donnell

On December 22, 1849, The Illustrated London News ran a story about a woman named Bridget O’Donnell, a famine victim from County Clare in the south of Ireland. In this piece, perhaps the first human interest story in the British press, Bridget recounted the horrors of the Irish famine, telling her own story of poverty, hunger, and destitution. The family had been evicted from their home when they were unable to pay their rent, and the corn grown by her family was taken from them and sold. As a result of the shock, and her weakened state, Bridget went into early labour, and her child was stillborn. Shortly afterwards she watched her 13-year old son starve to death. Bridget’s fate after the interview is unknown, but her story resonated throughout British society and drew attention to the horrors of the famine and the terrible toll it was taking on Ireland’s poor.

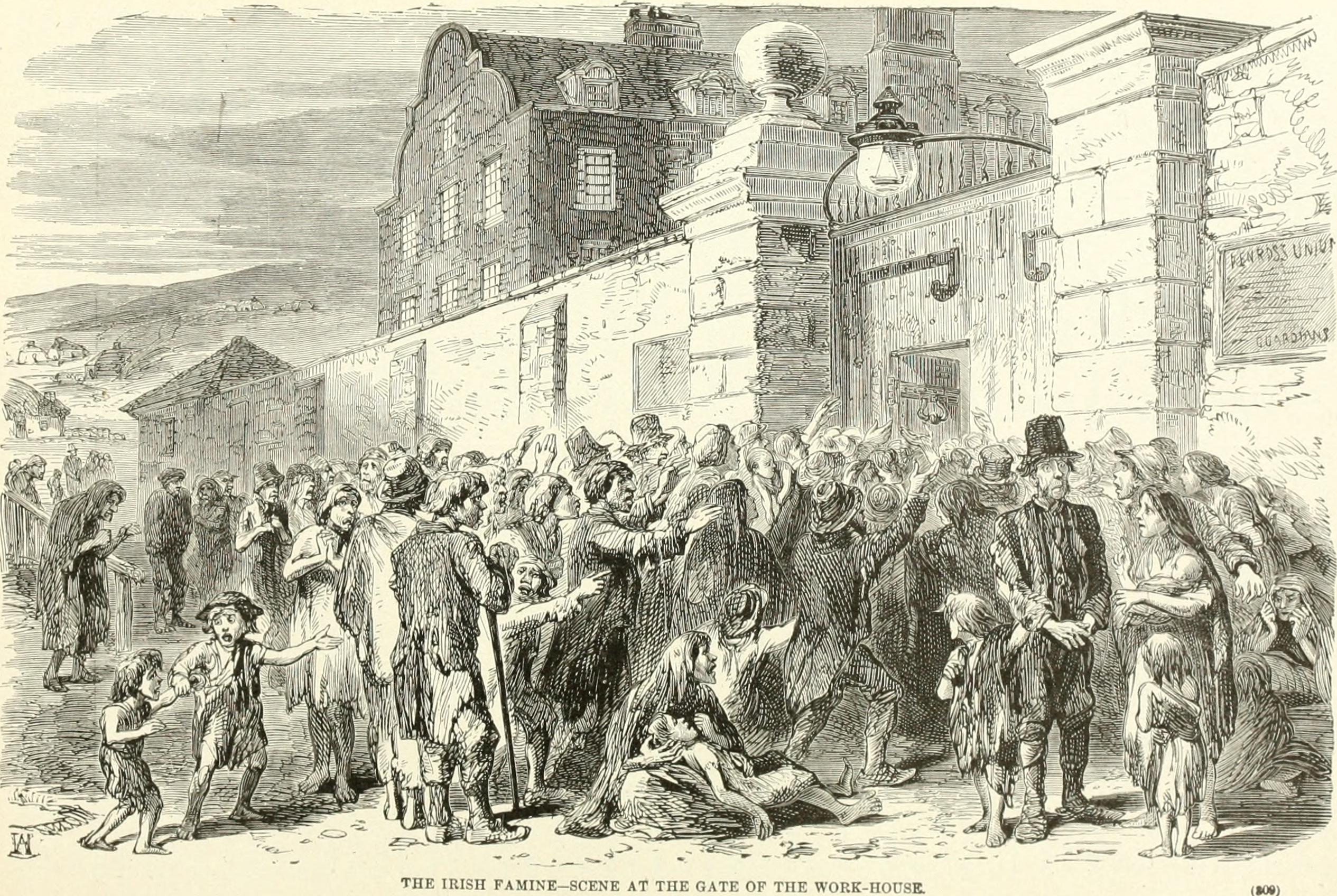

Prior to this exposé, public responses to the famine had been somewhat muted, following the government-led narrative that the catastrophe was the fault of the Irish, as a result of their laziness and primitive landholding system. The British public appeared to be inured to the horrors of the situation, and the crisis received little attention in the British popular press. However, the visceral image of Bridget, an innocent victim of the catastrophe, proved to be especially moving, and following this, public attitudes in Britain began to change, and the pattern of reporting on the crisis became more emotive and more frequent. Even Queen Victoria decided to pay a visit to Ireland in the summer of 1849, in order to show compassion for the victims and reassert herself as a symbol of British rule and paternalism.

Rebellion: The Young Irelanders

In the summer of 1848, the political situation in Ireland reached a point of peak tension. The hardship of the famine and the failure of successive British leaders and Irish administrators to mitigate the crisis led to widespread anger and resentment. In February, the French king Louis-Philippe had been deposed, and the Second Republic proclaimed in Paris. Europe was seething with rebellion, as large numbers of people across the continent protested against autocratic government and demanded rights and suffrage. In this context of liberal romanticism, calls for Irish independence were reinvigorated. A group known as the Young Irelanders broke away from the Repeal Association headed by Daniel O’Connell and began to agitate for full Irish independence.

Two of the leaders of the movement, William Smith O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher, gathered support from France and liberal movements in Britain. They hoped for a bloodless rising in Ireland that would establish an Irish parliament with full executive and legislative powers, independent of Westminster. However, on 22 July 1848, the government suspended Habeas Corpus in Ireland, allowing them to detain the leaders of the movement at will. The rising descended into violence.

Matters came to a head in the village of the Commons in County Tipperary on the 28th July 1948. The Young Irelanders had moved through County Wexford and County Kilkenny, rousing support for the cause. When the police and military forces arrived in Tipperary to arrest the leaders of the revolt, they were alarmed at the size of the crowd and took refuge in a large, nearby farmhouse, taking a local family hostage. This provided them with a strong defensive position, which the rebels were unable to penetrate. After hours of intense fighting, the rebel ammunition was dwindling, and as further police reinforcements arrived, they abandoned the siege and fled. The leaders of the rising were captured, tried, and deported, effectively crushing the Young Irelander movement, and stifling further calls for repeal.

The Young Irelander movement did, however, have significant consequences. Members of the group who had fled overseas became leaders of Irish nationalist movements in the diaspora. Three such figures, Michael Doheny, John O’Mahony and James Stephens founded the Fenian movement, which would foment further unrest in Ireland in the latter half of the 19th century, and eventually spark the 1916 Easter Rising that would lead to Irish independence. The Famine was a key driver of these events, creating a palpable sense of anger and resentment at the British that would pass into historical memory and folk legend, fuelling calls for rebellion.

Legacy

By 1849, the famine was over, but the effects on Irish society would endure long into the future. The Irish were shell-shocked by the catastrophe, and for several decades, the nationalist movement lacked coherent organisation and leadership. However, the memory of the famine became enshrined in local memory and ultimately served as a rallying motif for nationalist and independence movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The famine permanently changed the demographic, political and cultural landscape of Ireland, creating echoes that endure to the present day.

The major problems exposed by the famine centred on the issue of land distribution and tenants rights. In the 1870s, the land reform movement began to gain popular support, with the leaders appealing to the traumatic memory of the famine in order to gain support for their cause. This was particularly effective during the depression of 1879 when a fall in profits threatened the livelihoods of tenant farmers once again. The memory of the famine fostered popular support for the issues of land reform and which had now become explicitly linked to social issues. Increasing numbers of Irish saw themselves as victims of a brutal regime and believed that their only hope of emancipation was through home rule. Once again, in the years preceding the Easter Rising of 1916, Irish rebels drew of the potent imagery of the famine to justify their actions and draw support for their cause.

The memory of the famine, therefore, played a pivotal role in defining the political upheaval and violence in Ireland of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Furthermore, it remains a powerful scar on Irish politics to this day, fostering mistrust between Catholic and Protestant communities in Northern Ireland, where systemic inequalities still persist. The memory of the famine stirs resentment against Protestant and Unionist communities. The old refrain, coined by the Young Irelander leader John Mitchel, still rings true in the ears of many Irish citizens: “The Almighty, indeed, brought the blight, but the English brought the famine”.

Sites to Visit

- The Doagh Famine Village in County Donegal, close to Londonderry, is a fascinating outdoor museum that recreates the visceral image of life for an ordinary family during the famine. Similarly, the Strokestown Park Famine Museum in County Roscommon contains a remarkable set of letters between tenant farmers and landlords, which bring to life characters from the past and make strong links between the Irish famine and present-day hunger and suffering in societies across the world.

- The Jeanie Johnston Tall Ship and Famine Museum in Dublin contains a real example of a ‘coffin ship’, enabling visitors to see what life was like onboard one of the many ships that sailed to the Americas in this period.

- The Famine Warehouse in Ballingarry, County Tipperary, is the site of the last stand of the Young Irelanders and offers guided tours and information about the rebellion.

Film, Literature and TV

- The Whitest Flower – a seminal novel by Brendan Graham (1998).

- The ITV series Victoria features an episode on the famine, and the British response (2017).

- The Hanging Gale – a four-episode Irish television show, which aired in 1995. It covers the story of a tenant farming family during the famine.

Further Research

- James Donnelly, The Great Irish Potato Famine, (Sutton Publishing, 2002). A comprehensive account of the famine.

- Colm Toibin and Diarmaid Ferriter, The Irish Famine: A Documentary, (Profile Books, 2004). An excellent narrative of the famine and a collection of documents from the period.

- Christine Kinealy, The Great Irish Famine: Impact, Ideology and Rebellion (Palgrave, 2002). Kinealy broadens the focus to look more widely at the causes and implications of the famine, and the rise of later conflicts in Irish history.

YouTube Videos

The Great Famine: BBC Documentary (1995)

The Great Irish Famine: Who’s To Blame?: Irish Radio Documentary